The National Statistics Council (a body established under the Statistics Act to offer advice to Chief Statistician) has suggested a compromise that would mean leaving the census mandatory, relaxing penalties for non-compliance (no more jail time threats), and removing Question 33 about unpaid work from the 2011 Census.

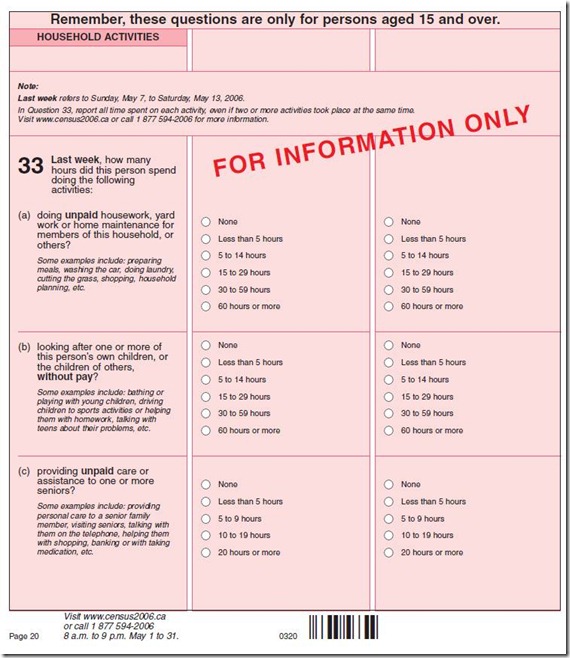

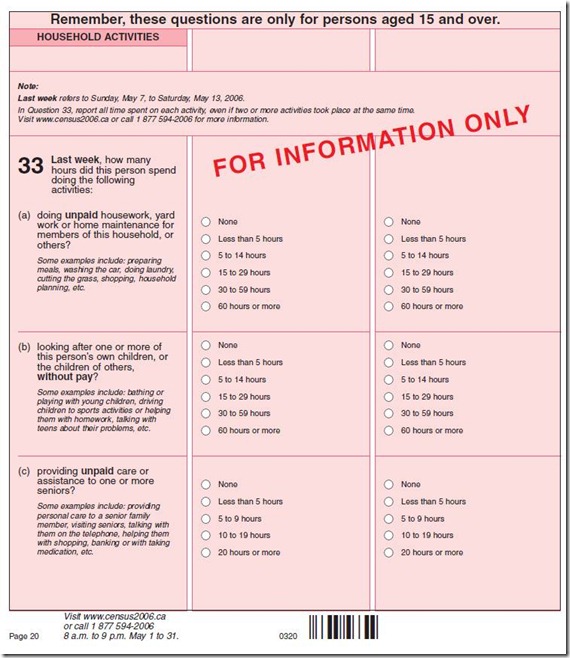

I have serious concerns about eliminating Question 33, which tries to capture the extent of women’s role as primary caregivers in society. Question 33 (see the question below) asks about unpaid household work, time spent looking after children, and providing care for elderly parents. Removing this question from the Census in 2011, as suggested by the National Statistics Council, will be a great disservice to Canadian women, who indeed account for most unpaid work, and therefore face the trade off between pursuing corporate careers and taking care of the vulnerable in the society, i.e., children and elderly.

In its recommendations, the Council should have suggested an alternative (a new survey perhaps or modifying the existing surveys, such as the one on volunteering, etc.) to eliminating Question 33.

Also, I wonder how many women serve on the National Statistics Council and what was the reaction of those women about the suggestion to axe Question 33 about the unpaid work.

Question 33 in the Census long form.

Two-times as many women than men work unpaid for more than 15 hours/week

According to Statistics Canada:

| Unpaid work in Canada | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 |

| % of males reporting any hour(s) of unpaid work | 86.7 | 88.4 | 89.5 |

| % of females reporting any hour(s) of unpaid work | 93.2 | 93.4 | 93.5 |

The 2001 Census presents a breakdown of the weekly unpaid work by gender. The numbers below suggest that the category of longest duration of unpaid work (15 hours or more) is heavily dominated by women. For instance, 45% women and only 23% men reported working for more than 15 hours for unpaid work.

| 2001 Census | Total | Male | Female |

| Individuals eligible for answering Question 33 | 23,901,360 | 11,626,785 | 12,274,570 |

| No hours of unpaid housework | 10% | 13% | 8% |

| Less than 5 hours of unpaid housework | 24% | 30% | 17% |

| 5 to 14 hours of unpaid housework | 32% | 33% | 30% |

| 15 to 29 hours of unpaid housework | 20% | 15% | 24% |

| 30 to 59 hours of unpaid housework | 11% | 6% | 15% |

| 60 hours or more of unpaid housework | 4% | 2% | 6% |

| Total - Hours spent looking after children, without pay | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| No hours of unpaid child care | 62% | 66% | 58% |

| Less than 5 hours of unpaid child care | 10% | 11% | 9% |

| 5 to 14 hours of unpaid child care | 10% | 10% | 9% |

| 15 to 29 hours of unpaid child care | 7% | 6% | 7% |

| 30 to 59 hours of unpaid child care | 5% | 4% | 6% |

| 60 hours or more of unpaid child care | 6% | 3% | 10% |

| Total - Hours spent providing unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| No hours of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 82% | 85% | 79% |

| Less than 5 hours of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 12% | 10% | 13% |

| 5 to 9 hours of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 4% | 3% | 5% |

| 10 to 19 hours of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| 20 hours or more of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Statistics Canada - Cat. No. 95F0390XCB2001004 | | | |

The 2006 data are presented below:

| 2006 Census | Total - Sex | Male | Female |

| 2006, total individuals over 15 years | 25,511,870 | 12,395,135 | 13,116,740 |

| No hours of unpaid housework | 10% | 12% | 7% |

| Less than 5 hours of unpaid housework | 24% | 30% | 18% |

| 5 to 14 hours of unpaid housework | 32% | 34% | 31% |

| 15 to 29 hours of unpaid housework | 20% | 16% | 24% |

| 30 to 59 hours of unpaid housework | 10% | 6% | 14% |

| 60 hours or more of unpaid housework | 4% | 2% | 6% |

| Total - Hours spent looking after children, without pay | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| No hours of unpaid child care | 62% | 66% | 59% |

| Less than 5 hours of unpaid child care | 10% | 10% | 9% |

| 5 to 14 hours of unpaid child care | 9% | 10% | 9% |

| 15 to 29 hours of unpaid child care | 7% | 7% | 7% |

| 30 to 59 hours of unpaid child care | 5% | 4% | 6% |

| 60 hours or more of unpaid child care | 7% | 3% | 10% |

| Total - Hours spent providing unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| No hours of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 82% | 84% | 79% |

| Less than 5 hours of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 11% | 11% | 12% |

| 5 to 9 hours of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 4% | 3% | 5% |

| 10 to 19 hours of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| 20 hours or more of unpaid care or assistance to seniors | 2% | 1% | 2% |

Source: Statistics Canada - 2006 Census. Catalogue Number 97-559-XCB2006007.

---------

For those interested in determining the efforts behind getting the question 33 added to the census, I suggest the following article from Studies in Political Economy:

Studies in Political Economy, Vol 56 (1998)

Where Women's Efforts Count: The 1996 Census Campaign and "Family Politics" in Canada

Meg Luxton, Leah F. Vusko

Abstract

After more than ten years of organising and lobbying by women's groups, the 1996 Canadian Census included, for the first time, a detailed question about the amount of time people spend on unpaid housework and care giving for children and seniors. According to Statistics Canada, this information was collected to "provide a better understanding of how these unpaid activities contribute to the well-being of Canadians." However, behind this formal explanation lies an on-going political struggle over who is or should be responsible for the socially necessary work of taking care of people, especially dependent children and elders, and how that work should be socially recognized and organised.

Full Text: PDF

Studies in Political Economy:

Online ISSN 1918-7033

Print ISSN 0707-8552

Some background on unpaid work question in Census

The motivation came from the United Nations:

“International Developments The roots of the 1996 Census campaign may be traced to the Third United Nations World Conference on Women in Nairobi in 1985 where the International Wages for Housework Campaign presented a motion that led to the UN resolution contained in paragraphs 58, 64, 20, 130 and 179 of the Forward-Looking Strategies for the Advancement of Women. This resolution directed countries to:

- provide gender specific data;

- recognise the remunerated and unremunerated contributions of women in national economic statistics and the gross domestic product, especially those contributions of women in agriculture, food production, reproduction, and household activities;

- improve the capabilities of national statistical institutions to implement these concepts and measure regular programs;

- strengthen, monitor and evaluate statistics and indicators on women; and

- provide training for producers and users of statistics on women.”

Carol Lees, an unsung hero

“At this juncture, Saskatchewan homemaker Carol Lees refused to fill out the 1991Census because it did not recognise her unpaid domestic work. Picketing a federal government building in Saskatoon and challenging the government to arrest her, her efforts attracted support from other women's groups - for example, the Saskatchewan executive of the National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC) picketed with her - and generated widespread media coverage.”

Statistics Canada did background research

“Statistics Canada also held an international conference in April 1993 on the "Measurement and Valuation of Unpaid Work."24 Billed as a conference of international "experts," women activists in Canada were .initially not invited. For many women, this experience of exclusion reaffirmed the government's dismissive attitude towards women's groups and their concerns. However, many women protested and, eventually, invitations were extended to representatives from ten women's organisations.”

Statistics Canada reluctant to add question on unpaid work

“Statistics Canada took the position that the Census was an inappropriate place to measure unpaid work upon completing extensive consultations and a Census Pre-Test. In making this assessment, Statistics Canada suggested that the Pre-Test indicated that a Census question on unpaid work, "was liable to produce inaccurate and insufficient data as well as results that were ill-suited to guiding public policy-making and further research on unpaid work."54 Subsequently defending its views to the media, Assistant Chief Statistician Bruce Petrie noted that "testing to date has shown that the Census is not the appropriate vehicle for collecting data of this type.”

The Parliament over-rules Statistics Canada on unpaid work

“Cabinet was scheduled to make its decision early in 1995. However, it repeatedly delayed its announcement. Finally, during the Fourth United Nations World Conference on Women in Beijing, where Canadian delegates were in the leadership in negotiating new language on measuring and valuing unpaid work the Canadian government announced its decision to add a question to the 1996 Census. In a rare move, it had overruled Statistics Canada. Cabinet did not give any explanation either for the delay or for the basis of its decision. For undeclared reasons, the Canadian government appeared to respond to political lobbying from women's groups, against the advice of Statistics Canada, and made its announcement at the height of international attention.”

The National Statistics Council presented the following recommendation to the government:

Seeking Solutions by NSC

The National Statistics Council, the senior, external advisory group appointed by the government of Canada to advise the Chief Statistician, is deeply concerned by the effect of the announced changes to the 2011 Census. We believe that the changes will harm the integrity and quality of the Canadian statistical system. At the same time, the Council recognizes that concerns about intrusiveness and confidentiality should be addressed.

It is urgent we find solutions that protect the quality of the information Canadians depend upon while responding to concerns over the way in which the Census is conducted.

What is at risk?

First, the proposed, voluntary National Household Survey will suffer from significant respondent self-selection bias. Even with substantial efforts to mitigate the inevitable decline in response rates, this will degrade the data upon which much of the Canadian statistical system is based.

The proposed changes will likely result in Statistics Canada’s not being able to publish robust, detailed information for neighbourhoods, towns or rural areas. Much of the analytic work done by municipalities, private firms, health agencies, highway and transportation planners, school boards and large numbers of other groups that depend upon small-area knowledge and data will no longer be possible.

Our second concern is the potential loss of vital benchmark information. The mandatory ‘long form’ means that Statistics Canada has an accurate benchmark for the demographics of populations who are difficult to reach or who are less likely to complete a voluntary survey. This, in turn, means that sampling and weighting strategies for subsequent, voluntary surveys can compensate for differential response rates and produce more reliable information.

The importance of having Census benchmarks available is readily apparent when one considers some of the populations that we know are more difficult to reach – young people making the school-to-work transition, urban Aboriginal populations, the affluent, and new immigrants.

Without solid benchmark information, subsequent surveys and analysis rest on an uncertain foundation. The Bank of Canada cautiously stated that, while they do not use long-form data directly, they feel they will have to evaluate “the impact that any proposed change would have on the reliability and the quality” of economic data they use. The Bank’s statement exemplifies the repercussions the changes may have over the broader Canadian statistical system.

The National Statistics Council also recognizes the concern that Canadians not be overburdened by governments compelling them to respond to onerous or intrusive demands for unnecessary information. On a number of occasions, the National Statistics Council has urged changes and worked with Statistics Canada to reduce such respondent burden. With respect to the Census, the Council has strongly supported changes to data collection methods that enhance privacy such as mail-in and on-line options.

In addition, the Council strongly supports Statistics Canada’s commitment to the complete confidentiality of respondent information and it recognizes the agency’s undisputed success in reaching this goal. The Council shares the Privacy Commissioner’s Office view that Census questions are ‘inherently privacy-invasive’ and that the questions must be kept to what is necessary for good government and that the information gathered must be protected with the appropriate safeguards.

This focus on minimizing intrusiveness and protecting privacy is important to retaining the confidence of Canadians. We are satisfied that Canadians trust Statistics Canada and its procedures and that Canadians provide answers they would be unwilling to provide to a private survey firm. The Council also believes that confidence must be sustained through ongoing actions.

In a matter of a very few weeks at most, it will be impossible to change the 2011 Census or the National Household Survey. Meanwhile, debate over the future course of the Census has become heated without moving towards a resolution that meets both concerns about privacy and intrusiveness, as well as the need to maintain the quality of Canada’s statistical system. What then do we recommend?

The National Statistics Council recommends:

- That, as part of a formal consultation process beginning with the 2016 Census, Statistics Canada examine each Census question to ensure that it, at a minimum, meets one of the following tests for inclusion in the Census:

- It is required by legislation or Cabinet direction,

- It is needed for small-area data uses for which there is no alternative data source,

- It is needed to create benchmarks for measuring difficult-to-reach groups and ensuring that subsequent surveys or data derived from administrative sources can be sampled or weighted to reflect accurately the overall population,

- It is needed to assess progress on issues of national importance, for example the economic integration of new immigrants, or

- It is to be used as a basis for post-censal survey sampling of relatively small or dispersed groups, for example, urban Aboriginals or people with health conditions that limit their activity.

Even if a question met this requirement, it would still face tests of its overall importance to the Canadian statistical system and the needs of data users as weighed against cost and the intrusiveness of the question.

- The Council is aware that other countries have conducted successful censuses without people having to face the potential of jail as a punishment for not filling out census forms. We, therefore, recommend that the Statistics Act be amended to remove jail sentences as a possible punishment for not filling out the Census. At the same time, the Council recommends that jail continue to be a punishment for those who wilfully break confidentiality provisions.

- That the Census for 2011 include the long form being used for 20% of the population as the only way, given the very short timeframe, to safeguard the quality of the Canadian statistical system.

- That the question series on household activities (question 33 in the 2006 long-form Census) be dropped as it was the question that occasioned the largest number of objections among the substantive questions and since it fails to meet any of the five tests outlined in point 1.

The National Statistics Council believes that these steps, taken together, can respect the valid concerns voiced by Canadians about privacy and intrusiveness, while ensuring that the vital information that currently flows from the long-form Census can be maintained and continues to serve Canadians’ needs.

Ian McKinnon,

Chair, The National Statistics Council

National Statistics Council

Establishment of the National Statistics Council

In the early 1980s Statistics Canada embarked on a conscious program of strengthening its active consultative mechanisms with key clients and broadly based representatives of the national interest. Among the major new initiatives were the establishment of a series of bilateral senior committees with key federal departments – both clients and sources of data derived from administrative records (this supplemented already existing strong consultative mechanisms with the provinces); and some 10-15 professional advisory committees were set up. The latter involved experts (typically from outside government) in such areas as demography, labour, national accounting, price measurement, service industries, etc.

In 1985, the government established, at the apex of the Agency's consultative mechanisms, the National Statistics Council. Its formal mandate is very brief: it is to "advise the Chief Statistician in setting priorities and rationalizing Statistics Canada programs". In line with other aspects of Canadian policy in relation to statistical activities, a careful balance was attempted between policy relevance and professional independence.

Appointment process and membership

Members of the Council are appointed for a period of three years but subject to renewal. There are about 40 members. While there are no rules for representation, the following practice has generally been adhered to:

- All members serve in their individual capacities – there are no formal representational appointments;

- Most members are interested and prestigious analysts of some aspect of Canadian life, but few are professional statisticians;

- Some members from Statistics Canada's various professional advisory committees serve on the Council. This ensures the availability of a wide range of subject matter knowledge within the Council, as well as linkage with the Agency's other advisory bodies;

- A senior member from the Statistical Society of Canada sometimes serves;

- At least one senior journalist on social or economic affairs is a member;

- Membership is selected in such a fashion as to ensure appropriate knowledge of the different provinces and territories of Canada ;

- No federal official is a member of the Council. This enhances the de facto independence of Council to "speak up" should it be necessary;

- The Chief Statistician is an ex officio member;

- An Assistant Chief Statistician serves as secretary.

A large proportion of the initial members, were appointed by the Minister from a list of persons recommended by the Chief Statistician. Subsequent appointments have been proposed to the Minister by the Chief Statistician following discussions with the Chairman of the Council.

As a result of these measures, the Council is a very knowledgeable, influential and broadly representative group. Indeed, its influence derives from the individual prestige of its members.

Agenda and Modus Operandi

The Council normally meets twice a year, each time for a day and a half. Regular agenda items are “Statements by Members” in which Council members may raise questions or concerns either for immediate response or subsequent discussion, and an in-depth report by the Chief Statistician on recent developments at Statistics Canada (including new substantive initiatives, forward planning, budgetary expectations). Other agenda items usually deal with major statistical or policy issues – such as: Census content, Environment statistics, Longitudinal data, Issues in social statistics, National accounts, Dissemination practices, Pricing policy, Privacy and record linkage, Contingency planning in the face of expected budget cuts, the Provincial component of the national statistical system, Significant statistical information gaps, etc.

Agenda items are selected from items raised by members and issues identified by Statistics Canada in discussions with the Chairman. From time to time a subgroup of the Council is formed to deal with particular issues (e.g. access to historical censuses) between Council meetings.

The Council generally provides feedback to the Chief Statistician through a discussion among its members. Consensus is usually (though not always) achieved.

Conclusion

There can be no doubt that members of the Council take their function seriously. The Chief Statistician regards their advice as being of very substantial benefit. In addition, through the prestige of its members and through precedent, Council has evolved into an additional and – should the need arise undoubtedly very influential – bulwark in the defence of the objectivity, integrity and long-term soundness of Canada’s national statistical system.